Indigenous People’s Day Weekend at Sugarloaf

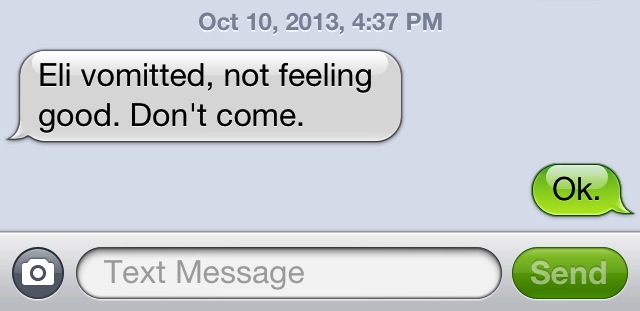

The weekend got off to an early start with a rare and welcome tutoring cancellation.

The motherlode of my nascent climbing rack (the Camelots!) had arrived earlier in the week. As if by magic, I managed to turn stuff like this:

Into stuff like this:

Before buying the gear, I consulted a half-dozen trusted climbers in my trusted climbing community, all of whom were conveniently gathered in one extremely inconvenient location. They were very opinionated and contradicted one another. I should have doubles from #3 down to .5. No, I should have doubles down to .4. No, I should not have a .4 at all. I should have a .4, but it should be an X4, not a C4. I should have Metolious master cams. I should not have Metolious master cams. I would need master cams, but only if and when I did a big wall. Offsets were indispensable. Offsets were unnecessary. For small stuff, TCUs, definitely. No, Aliens, obviously! C3’s were great. C3s sucked. C3’s were irrelevant now that there were X4’s. C3’s were still relevant.

When they began contradicting even themselves, I realized that there was no one right answer, and, as Rilke said, I would have to live the questions. I sat down in front of a computer, availed myself of a discount, and put some shiny objects that were the same as the ones most everyone else seemed to have into a virtual shopping cart. I am not ashamed to admit I had my hand literally held during this process.

I spent the rest of the week arranging and re-arranging the cams on my coffee table, testing which of my furnishings could bear their combined weight on a single sling, and sleeping with them in my bed with me in batches. If co-sleeping cements bonds between humans, I reason, then surely there is some spiritual merit to practicing this with inanimate objects. So far it’s worked with my rope, the Holy Guacamole, shown here tucked in on the first night of our life together, still factory-coiled:

As I read, wrote, cooked, and computed, I would periodically pick up the cams and squeeze their triggers, thinking, “Which of you will be the first to save my life?”

On the eve of their first trip out, I threw myself a little going-away party. I don’t get many visitors at the tiny house, so I was the sole attendee. I watched the video Jacob posted on my Facebook wall for psych. I pored over the guidebook, looking for the perfect pitch of 5.8 (my current trad lead limit/plateau) on which to take the shine off my gear, then devoured online back issues of Rock & Ice, seeking lifesaving tips.

In the midst of my rituals, I took a phone call from James, the individual I hold responsible for gateway-drugging me into this addiction. We don’t communicate often, but when we do, it always feels like espionage.

“I hear you’re going climbing,” said the familiar voice. “I called to wish you luck.”

“I’ll need it,” I said. “I just got my own cams.”

“Now you can take HUGE FALLS on them,” he chuckled.

As usual, James’s dangerous laugh made me feel strangely safe. His own method of learning to lead was to climb Tuolumne runouts with a single set of cams, routinely reducing anchors to two pieces, or sometimes, he alarmingly shrugged, even one. Among his other unorthodox opinions is that a severe Giardia infection can double as a Master Cleanse.

Compared to these practices, my shiny new doubles and intention to build textbook three-piece anchors suddenly seemed the equivalent of a protective bubble, though it was actually just normal, to whatever extent that climbing up a vertical rock and then trusting your life to a bunch of metal objects you stick in some cracks, some 8mm-wide nylon, a guy you can’t always see, and most/worst/best of all, yourself and your own decisions, mental fortitude and will to live can be said to be normal.

“They say learning to lead is the most dangerous time in your climbing career,” I fretted.

“Well, you’re well past that,” James replied, charitably referring to the one 5.8 I had onsighted so far, a feat I performed after getting lost for nearly an hour on the alpine approach.

Thus blessed, I continued my evening. With only a single Sierra in the tiny fridge, I soon got into the whiskey. Somewhat blitzed and sufficiently blazed, I watched several hours of climbing videos depicting feats I will not achieve in this lifetime, hoping to absorb the single sentence that might come back to me, Lebowski-style, at a crucial moment.

I talk myself through cruxes by whispering things I’ve heard other people say like mantras. For a while, the only climbing-related phrase I knew was “Spread your legs and trust the rubber.” It was of great comfort to me. This time, it turned out be Lynn Hill saying, “Don’t rush the move.” This all went on until 4 a.m., and then I was so excited and scared I couldn’t go to sleep until 5.

*

The next afternoon, we massed at Jacob’s house on a suburban dead end. For the first time, I wasn’t the only female on the trip. Summer began taking things out of the trunk of her Toyota, things that greatly resembled the things in the back of SubyRuby. “I’m kind of prepared for everything, all the time,” she said, almost apologetically, winning me over immediately.

We packed Jacob’s car, pre-partied by his mom’s pool and made the obligatory Trader Joe’s stop for tortillas and salami before heading to Sacramento to rendezvous with Clark. After In-N-Out burgers, we arrived at the bivy shortly before midnight and bedded down. At 4:30 a.m., we awoke to rain that quickly turned to sleet. I had a horrible thought: maybe the rest of the group would see this as an opportunity to get an alpine start. But luckily, everyone piled back into the car to cuddle-puddle until a reasonable post-dawn hour.

Once we set off, I got mildly lost on the approach. Summer retrieved me from where I was wandering on the wrong side of the formation and we laid out the gear at the base of a 5.7 for me and Clark to start with, next to a 5.9 for Jacob to warm up on. The 5.7 started with an runout chimney. This was exactly the kind of thing I would normally defer to Clark to lead, i.e., anything less than perfectly protectable.

“The second pitch looks good,” I said hopefully.

“I want that one,” said Clark. “You already said you’re leading Pony Express.” This was the 5.8 I had selected.

It seemed wrong, somehow, not to place all that shiny gear immediately, and wronger still not to do my part leading my share of less-choice pitches. I could almost see my training wheels skittering down the side of the mountain as I started racking up.

Jacob was already near the top of the adjacent route by the time I tied in. I was inspired by his effort. “This is kind of physical,” he was muttering. That meant it was hard. If it were easier, Jacob would say, “This is pretty mellow.” The Jacob Decimal System ranges from “pretty mellow” to “kind of physical.”

The SuperTopo said that the chimney should be climbed “outside, while reaching in to place gear,” but this had probably been written by some tall male with an ape arm. I placed a cam in the bottom of the chimney, but once I established myself in it, there was no way I could reach into its crease.

One of my earliest pseudo-leads came back to me. Three Brits, a U.S. Marine and I had all taken off from the Valley for a road trip to the East Side. We stopped in Tuolumne to climb a an easy but runout route on Stately Pleasure Dome in what the Brits described as a “gongshow.” The day before, one of the Brits had taken me over to Swan Slabs and begun teaching me to place gear. The other two had come with folding chairs and beers to watch. When I promptly got a cam stuck, they freed it with an ice axe. Then, for my second lead, two of them, both 5.11 climbers, soloed next to me while I learned to place gear. (I am often reminded that such luxuries are a perk of being a novel female in a male-dominated environment.) Or rather, they soloed next to me while I climbed with gear on my harness while attached to a rope that was below me. The climb was so runout there was nowhere to put the gear. Then, a thunderstorm came in, and we took shelter in a chimney, ate chips and salsa, swigged tequila and took a smoke break.

Now, in my own chimney, I thought fondly of my safety-soloers, long gone with my training wheels. Ralph was digging wells and putting up new routes in the Ugandan jungle and John was conducting a systematic vertical exploration of Patagonia. But this chimney was only a fraction the length of that runout in Tuolumne, and far more secure. There was at least some gear, and no thunderstorm, nor tequila. I could see the part at the top that would feel good to grab. Up I went. For a moment, I was genuinely scared. To fall now would be inopportune, and unpleasant. I understood, both mentally and physically, that the way to cope with my fear of falling was not to fall and more importantly, not to stop. The seconds were long. As my eyes came over the horizon of the top of the chimney, I saw the next mountainside, the road below, the world at large. Born again.

I brought Clark up and he led the next pitch. “Where’s the walkoff?” I asked when I arrived at the belay.

“There’s another pitch,” said Clark. In my haste and excitement about the chimney runout, I had tossed aside the guidebook after reading about the first pitch. I had already learned the hard way during a recent epic on Eichorn’s Pinnacle that incomplete knowledge of the descent and total dependence on one’s partner could be problematic. Or I thought I had learned this.

Clark set off on lead.

“You’re on belay,” he said, too soon, from above. “But I’m not sure this is the end.”

“Do you see a walkoff?” I shouted up.

“Not really,” said Clark.

“Next time we’re bringing the book,” I said testily, noting that we were ironically engaged in the classic male/female “ask-for-directions” conflict, but in the vertical world.

“Are you sure you’re still on route?” I asked.

“No. But maybe we can just rap down.”

“No, we can’t! You can’t rap this route with one rope. It says so in the book. That part I remember.”

“If you guys can’t get down, you can just rap down to me,” came a voice.

“What?”

“You can just rap down to me. I’m on a ledge below you, and I’ve got two ropes we can rap on to the ground.”

I could hear this person, but not see him. “Hey,” I yelled toward the voice. “What’s your name?”

“Eric!”

Labor Day weekend, Jacob and I had climbed at nearby Lover’s Leap. While we ate lunch in the shade, a seasoned climber had come over to us, cracked open a beer, and held what amounted to a Climbing Story Hour. He chronicled every time his van had broken down in Benson, the town nearest to Cochise, a climbing area in Arizona. A tow-truck operator named Dave was a recurring character, and had the last word. Jacob and I, entranced, consumed most of a salami and all of a spliff.

“You can live the life you want,” concluded the seasoned climber. “It just takes some careful planning and management. Some people will hate you for it, though,” he added.

After we borrowed his pre-SuperTopo guidebook and selected Surrealistic Pillar Direct, his parting words to us were, “Well, I hope you guys have a great adventure!”

“When I get older,” I said to Jacob, “I wanna be that guy.” His name was Eric.

“Eric!” I shouted. “It’s Emily! Remember me?”

“Emily! Of course! Do you feel better now about rapping down here?”

“Much! I guess we got in a little over our heads,” I sighed.

“In over your head is the end of your rope with no rap station,” replied Eric cheerfully.

This might be true, but in the future, we could not hope that every time we got into a jam or lost our way, a seasoned climber we knew and trusted would appear with an extra rope and an open beer like a magical, shaggy fairy. (Could we?)

“I’m just gonna run up there, Eric, and see if I can’t find that walkoff.”

I climbed up to Clark’s belay and then asked him to feed out more slack. He had been looking for a chimney, but there was a tunnel directly ahead. I crawled through it and on the other side were ledges and an obvious descent. I yelled for more slack and started looking for a good place to make an anchor to belay Clark over. But I hadn’t stopped to get all the gear from Clark. I had only the #3 and #4 I had removed from the wide crack we had just climbed, and a double-length sling. I had an A-HA moment. This was just a puzzle–like the science team again, but outside, with worse consequences for failure, and beers at the end.

About a month before, Clark and I had gone out to Lovers Leap for our first climbing day all alone. We had always climbed before in the company of James or Jacob, our more experienced friends. As soon as they left us, we would often quickly get ourselves into some minor to major trouble. Once it was resolved, James would sneer, “That’s how you learn,” and Jacob would hug us.

I had been really scared that day we went without them, most of all to build natural anchors all by myself, even though I had been practicing, observing and reading about it for months. But my buddy had wise words.

“Just place three good pieces,” said Clark, “and let science take over.”

I remembered Ralph placing the first piece of gear in a crack in Squamish he was encouraging me to lead, but I was scared to. He rolled his eyes, stuck a cam in the crack and yanked on it.

“It’s not rocket science,” he shrugged.

“Science,” I thought, as I regarded the gear I had. “But not rocket science. Let non-rocket science take over.”

I found placements for the #3 and #4 and slung a rock with the sling. It was my first piece of natural pro, and looked just like the picture in my John Long Climbing Anchors book. I grinned from ear to ear, at no one. I belayed Clark over and we headed down, having climbed our third multi-pitch together, all by ourselves, without requiring rescue.

Back at our packs, Summer and Jacob informed us that on their climb, Summer had dislocated her shoulder.

“So I’ll be the belay bitch for the rest of the day,” she said.

Had I dislocated my shoulder, I would probably by that point be loudly demanding Vicodin. Summer must be very tough, I thought. She had also put hot cocoa in our morning coffee. My girl-crush intensified.

Jacob and Clark went off to indulge in some 5.10. We hung out with Eric and his partner for a while and they showed me how to pass a knot and stack nuts. “Learn your nutcraft,” said Eric, in that momentarily stern voice they always use when their bravado gives way to crucial information.

The daylight was waning. It was time for Pony Express. Summer insisted she could belay me with one arm; the dislocated shoulder wasn’t the brake hand.

My good feeling about Pony Express got even better when we arrived at the base. The giant flake beckoned in the afternoon sun. The rope was all in a pile on the ground. I would be the one to take it up there. I had never led anything without someone who knew more than me about climbing standing at the base, soothing me with the sound of their bored, vaguely amused voice, but now I was wholly in charge of this operation.

“You got this,” said Summer.

“I hope so,” I said.

I racked up and started up. I couldn’t believe this was allowed. I couldn’t believe I actually knew enough to do this. I missed, with an ache, the taut tug of the toprope. I looked, with a sick stomach, at the wet noodle of rope snaking below me. I experienced, with a bodily thrill, the elated relief of clipping that rope to something I wedged so tightly in the rock as to be immobile. I understood, as I climbed, why it was better “without the rope in your face.” I made each move with a quality of presence that was in and of itself a drug. By the time I had a few pieces in, this began to seem more–normal. Then I came to the business.

It was more serious business than I had seen before. A longer lieback, fewer feet, less rests, uncertain hands. I was standing on the last little ledge. There was certainly gear to be had. I reached up as high as I could and placed a #3. I pulled on it. “Bomber,” I murmured, comforted by the sound of my own voice whispering this word to the granite. I clipped the shiny silver carabiner to the cam’s brand-new brilliant blue webbing. I extended the still-white sling with its absurd red stripe as far as it went. I pulled up my green rope and clipped it to the other shiny silver carabiner. I was protected.

Now I had to consider how to climb beyond that blue object, to another place where I could remain, free a hand, and insert another object somewhere into the spaces in this rock. There was a place, up above, where this appeared possible. I had to get there.

I coaxed myself up off the rest on the few feet of toprope I had created. Then I was past the piece. But the next rest did not present itself easily. It was not as close as I had hoped, nor was I moving as fast as I would have liked to be. What had been working was no longer working. Upward progress stalled. My muscles were working, quite hard. I was starting to shake. Then I was shaking. Then I could not hold on. I wanted to. I willed myself to. But I could not. I reached up, but I was going down.

It was not so much a release as a failure of grip. Holding on became letting go. It happened against my will, but once it happened, I surrendered.

I do not remember the sensation of falling. I remember the sunlight sparkling on the granite’s black mica flecks in the moment before, the sound of my own breath and the smell of my own sweat, the inhuman noises of first the grunts and growls of effort and then the involuntary moans of slippage, the realization that these animal noises were mine.

I fell a not insignificant distance.

When the rope caught me, it was gentle and bouncy and fun. It was the endpoint of a split second during which my body believed at some level that it was all over. So it was a deliverance, a pardon, an awakening. As I fell, I had some time to consider whether or not I wanted to live. I did, very much. But I no longer had any choice, though I was responsible for what was happening in that moment, and what would happen next. I had to hope and trust. I had already let go. And in that brief, interminable, awful, wonderful fraction of a second, I tasted some new flavor of freedom.

I was always trying to let go of things—the past, the future, my ego, people I loved–but it seemed impossible. The only way I would ever let go of anything would be if I exhausted myself doing the opposite—holding on.

I was always raging against the system, how much I didn’t believe in it, didn’t trust it. “What are you going to do, make your own system?” people always said.

Yes. I would make my own system. This was the system I trusted–the one I made.

I hung from the #3, more exhilarated than frightened. Two spectators reclining on a rock below us whooped and cheered as I panted and trembled, adding further positive reinforcement to the experience. I felt a sharp pain in my right ankle and understood instantly why pretty much every climber I know has a messed-up ankle. The pain registered for a moment not as pain but as a sign of having a body. Then it disappeared completely.

I looked down at my belayer. “That’s the coolest thing I’ve ever seen in climbing,” she said.

“In some ways,” I said, “that’s the coolest thing I’ve ever done.”

I climbed back up to the rest from which I had placed the piece. It looked even more bomber now that it was actually serving its intended purpose. Now I just had to figure out why I had fallen off, and how to climb past it. I had fallen off because I had tried to layback where I should have been jamming. I saw now what would be a better way.

I made many false starts toward the crux, then finally powered through to a ledge. Once on the ledge, I realized that I had sewn the route up so much down low that I didn’t have much gear left for the remaining thirty or forty feet. “This is how I learn,” I sneered at myself. There were some bolts at the top of the adjacent route, about twenty feet below the bolts that ended my own route. I wanted desperately to clip them instead of climbing to the top.

Jacob and Clark had shown up and were grinning at me from below.

“Can’t I just clip those bolts?” I pleaded.

“That’s not a good idea, Em,” said Jacob calmly. “It could be 5.12 climbing to get to them. Better to just stay on route.”

I could hear the three of them talking and laughing down below and felt horribly lonely. Everything was all fun and games down there, while I was alone up here with my fear and my gear.

I placed one more piece as I powered to the anchor. In overdrive, I climbed right past the bolts at the end of my route by a good dozen feet, then downclimbed back to them. I suddenly felt like I could climb forever, and maybe like I needed to. Jacob and Clark shouted up that they would follow my rope and clean my gear, so I lowered off, admiring most of my brand-new rack, nestled in cracks, where it belonged. As is SOP after a Little Leader Learner takes a big whipper, my buddies prepared me a special present when I came in for a landing.

I leaned back against the wall, lit up, and felt the relief mix with the adrenaline, producing the ultimate natural speedball.

I loved Summer, for saving my life with one hand while I battled my own mind with my body for no good reason, hanging a rope she couldn’t even follow with her injured arm. I had known her for less than 24 hours, but now I felt as if we were bound by some kind of Samauri code. Was I responsible for her forever? Or was she responsible for me? Or was it both?

Summer and I went to retrieve our packs from the side of the formation. When we came back, Jacob was still trying to clean my gold nut.

“Did you weight this?” he asked.

“I jump-tested it,” I said. “Eric told me how to do it, so you know if it’s good to bail on. I wanted to give it a try.”

“It’s really in there,” said Jacob, with characteristic equanimity.

“Maybe I won’t do that anymore unless I’m actually planning to bail on it.”

“Maybe not,” said Jacob.

“It’s okay if you can’t get it,” I said.

The nut had cost $9.95 at REI. That was more than a beer, but less than a single cocktail in New York. And yet it sometimes seemed extremely important to retain or obtain these objects that cost more than a beer but less than a cocktail in New York, because sometimes this all seemed like a 3D video game, and these treasures extra lives. They were–or under certain circumstances, they could be. But it wasn’t a video game.

Jacob freed the nut and rapped the rest of the way down. We began our descent. As usual, I quickly got left in the dust. (At least when we are attached by ropes, and it really counts, my bigger, stronger, faster buddies can’t get more than 60m ahead.) But I didn’t fall too far behind this time.

“Where’s Emily?” I heard someone say.

“I am not going back for her,” said Clark, who is usually the one to go back for me. “How’s she gonna learn?”

“I’m right here!” I shouted, from a mere twenty feet away.

“Sorry, Emily,” said Clark, and gave me an apologetic hug.

We tromped out of the woods to the car and tailgated in the twilight while the cars sped by on Highway 50, circulating a Pale Ale and a Torpedo. Exactly twenty-four hours after our previous In-N-Out Burger, we were eating another.

When I finally got home and stepped out of my own car, a sharp pain shot up from my ankle, a whimper came out of my mouth, and I reflexively began hopping on the other foot. The ankle was badly sprained, but I had had enough adrenaline in my body that it took the combined time of our descent and drive from Strawberry to In-N-Out Burger Nowhere to Sacramento to Walnut Creek to Oakland for the pain to overpower my body’s natural painkillers, which had provided over four hours of total pain suppression.

“Good,” I thought. “Four hours is a long time. That’s long enough to get down from plenty far up–even at the rate I go.”